Air Pollution and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Mortality: A Stronger Association in Women than in Men

Article information

Dear Sir:

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a type of stroke caused primarily by the rupture of intracranial aneurysms. Although it has been actively investigated whether air pollution increases the risk of stroke, less attention has been paid to the specific relationship between air pollution and the risk of SAH [1,2]. Growing epidemiological evidence suggests that air pollution and medical conditions are associated differently in men and women, with women having a stronger association [3,4]. Because the female sex is considered a risk factor for aneurysm formation, SAH occurrence, and mortality [5], we hypothesized that sex-specific differential effects of air pollution would be prominent in women during the disease process of SAH. Thus, we aimed to examine sex differences in the association between air pollutant concentrations and mortality from SAH through a nationwide ecological study.

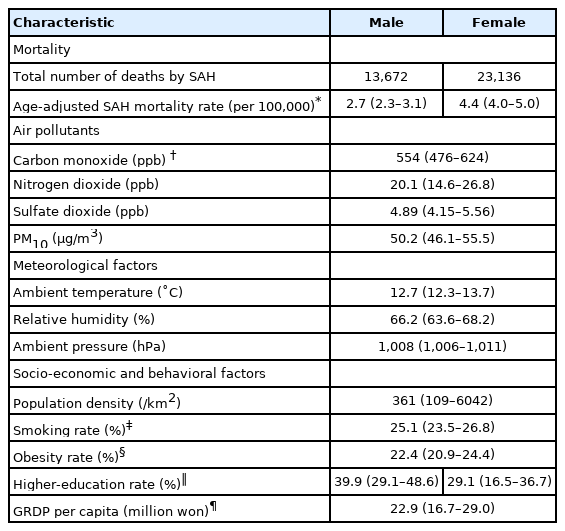

The study protocol was approved and the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board committee of Asan Medical Center (No. 2020-0851). The Korean Statistical Information Service (KOSIS) microdata system was used to obtain national mortality data between 2001 and 2018. The number of deaths from SAH was ascertained using the Korean Standard Classification of Diseases code I60. The data were provided per Si-Gun-Gu, which is comparable to the county system in the United States. The mortality rates were age-adjusted per 100,000 to the standard populations as of July 2010 in South Korea using a previously reported method [6]. Potential confounding factors such as population density, education rate, smoking rate, obesity rate as of the 2010 census, the prevalence of hypertension among the population (aged ≥30 years) (2008 to 2018), and gross regional domestic product per capita as of 2011 were also obtained from the KOSIS database for each district.

Air pollution data, including carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulfur dioxide (SO2), and particulate matter 10 µm or less in diameter (PM10) concentrations, from 332 measurement stations nationwide were obtained from the National Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Information System (http://www.airkorea.or.kr/index). The average of each pollutant per district was estimated using inverse-distance-weighted interpolation of nearby measurement stations from the longitudes and latitudes of administrative authority offices. The daily average ambient temperature, relative humidity, and pressure were obtained from the Korean Meteorological Administration database.

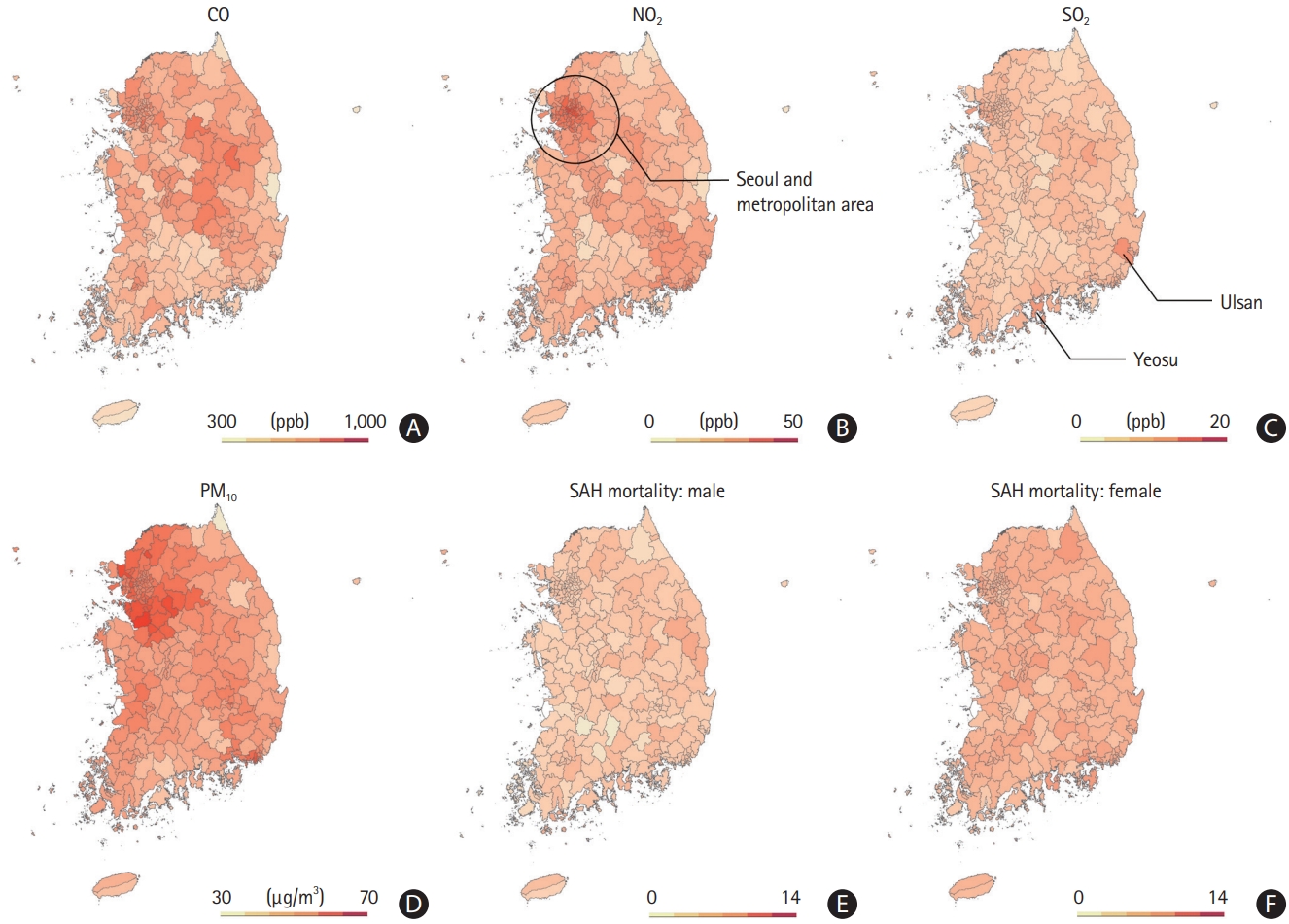

Between 2011 and 2018, 36,808 deaths were reported due to SAH, while the population of South Korea was 49,879,812 in the middle of the study period (2010) (Table 1). The spatial distributions of the air pollutant concentrations and age-adjusted mortality rates during the study period are shown in Figure 1. The NO2, CO, and PM10 concentrations were high in the metropolitan area surrounding Seoul. The CO concentrations were also high in the central region of South Korea, which has many cement factories. SO2 concentrations were similar across the country, except for Ulsan and Yeosu, which consume a large amount of ship oil because of their proximity to shipyards and the petrochemical industry.

Spatial distributions of the concentrations of (A) carbon monoxide, (B) nitrogen dioxide, (C) sulfur dioxide, and (D) particulate matter of size ≤10 µm, the mortality rates from subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) in the (E) males, and (F) females.

In a multivariable analysis of the association between air pollutants and SAH mortality, only SO2 concentration showed a significant association across all populations; a district with a higher interquartile range (IQR) SO2 concentration (1.41 ppb) had a 1.04 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.01 to 1.07) higher SAH mortality rate (Figure 2). When examined separately by sex, significant positive associations between NO2, SO2, and PM10 concentrations and female SAH mortality were identified, whereas all air pollutants exhibited null associations with male SAH mortality. A district with a higher IQR concentration of NO2 (12.2 ppb), SO2 (1.41 ppb), and PM10 (9.4 μg/m3) had 1.06 (IQR, 1.02 to 1.10), 1.06 (IQR, 1.03 to 1.10), and 1.05 (IQR, 1.01 to 1.09) fold higher mortality rates from SAH in females, respectively.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of estimated associations between age-adjusted subarachnoid hemorrhage mortality rate and air pollutants’ concentrations in (A) both the sexes and (B) male and females with multivariable beta-regression models controlling for population density, higher education rate, smoking rate, obesity rate, gross regional domestic production per capita, ambient temperature, humidity, and pressure per interquartile range change of air pollutant concentrations (carbon monoxide [CO] 148 ppb; nitrogen dioxide [NO2] 12.2 ppb; sulfur dioxide [SO2] 1.41 ppb; particulate matter 10 µm or less in diameter [PM10] 9.4 μg/m3) in males and females in 249 South Korean administrative districts between 2001 and 2018.

These findings suggest a close relationship between air pollution and SAH mortality, particularly in female patients. There are a few studies that have focused on the risk of SAH and have reported inconsistent results [1,2,7]. One study found an association in the short-term [2], but other studies reported null associations [1,7] between SAH mortality and air pollution in terms of months. The current study has the advantage of being based on data collected over the longest period on the largest scale in a nationwide manner. Moreover, for the first time, it was shown that the detrimental effects of air pollution on SAH may be more pronounced in women.

There are several possible mechanisms by which air pollution and brain hemorrhage are linked [2]. Air pollutants may cause direct ischemic damage to blood vessels or endothelial dysfunction, leading to vessel rupture. These may also trigger vasoconstriction and autonomic dysfunction, resulting in altered cardiovascular homeostasis. Moreover, the coughing caused by air pollution may increase intracranial pressure, which may lead to the rupture of vulnerable aneurysms. However, the prominent effect of air pollution on SAH mortality in women requires further investigation. Women are more likely to develop an intracranial aneurysm than men, and if they do, they tend to have multiple aneurysms [5]. In addition, women have higher overall mortality after the advent of SAH [5]. Meanwhile, women are known to be more vulnerable to air pollutants due to lower rates of smoking exposure than due to usual, smaller airways [8] with higher reactivity [9], and higher particulate matter deposition [10]. Therefore, women’s vulnerability to air pollution may have maximized their susceptibility to SAH mortality.

This study had several limitations. This study had an ecological design; thus, it should be used primarily to generate a hypothesis. With the current study design, interactions with sex could not be evaluated to determine the effect of air pollution on SAH mortality. Moreover, the generalizability is limited because of the lack of subject-level data for potential confounding factors. In this case, the unit of analysis is the district, not the patient. Finally, we were unable to assess the cumulative effect of air pollution and the long exposure lag period in this study. Further research is needed to consider the effect of air pollutants on SAH mortality according to various exposure durations and lag analyses. Nevertheless, our results suggest that the effects of air pollution on the disease process and outcome of intracranial aneurysms may differ by sex, which warrants future studies.

Notes

Disclosure

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, #2020OK9148.