Introduction

Fatty acids (FAs), the components of phospholipids in organelle and cellular membranes, play important biological roles by maintaining or processing membrane protein function or fluidity.1 In addition, FAs modulate vascular inflammation, a key mechanism of atherosclerosis, cerebral small vessel pathologies, and stroke, by altering intracellular signal transduction or controlling lipid mediators such as prostaglandins, thromboxanes, or leukotrienes.2 Among FAs, Žē3-polyunsaturated FAs (Žē3-PUFAs), such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), are potent anti-inflammatory molecules. EPA and DHA decrease expression of receptors for chemoattractants on blood inflammatory cells and prohibit migration of neutrophils or monocytes. Therefore, Žē3-PUFAs may protect from atherosclerotic changes.3,4

Several clinical studies have emphasized the role of FAs in the risk or occurrence of stroke5 or cardiovascular disease6; however, the effects due to the composition of FAs on stroke or cardiovascular disease remain controversial. High-dose Žē3-PUFAs has been reported to have beneficial effects on cardiac or sudden death.7 High levels of plasma Žē3-PUFAs can decrease the risk of myocardial infarction.8 In terms of stroke, low levels of circulating Žē3-PUFAs in the blood is a risk factor for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.9 A decreased proportion of linoleic acid is also associated with ischemic stroke.10 Compared to normal controls, stroke patients with moderate-to-severe intracranial arterial stenosis or occlusion had decreased levels of DHA.11 On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis revealed that the evidence for the beneficial effects of Žē3-PUFAs is insufficient in adults with peripheral arterial disease associated with poor cardiovascular outcome.12 To date, little information is available on the relationship between the composition of FAs and prognosis of stroke. Therefore, we investigated whether the composition of FAs was associated with stroke severity on hospital admission and functional outcomes at 3-months follow-up of patients with acute non-cardiogenic ischemic stroke.

Methods

Subjects

Between September 2007 and May 2010, we prospectively enrolled patients diagnosed with a first-episode of ischemic stroke and admitted to our hospital within 7 days after onset of symptoms. The patient's demographic information as well as past medical, medication and familial history; brain imaging studies (Computerized tomography [CT] and/or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]); vascular imaging studies (digital subtraction angiography, CT angiography, or MR angiography); chest radiography; 12-lead electrocardiography; electrocardiography monitoring during a median time period of 3 days at the intensive stroke care unit; transthoracic echocardiography; and routine blood test data were collected.13 Patients were preferentially excluded if they did not agree to provide blood samples for our study, or if they were taking lipid-lowering agents such as statins, niacin, fenofibrate, or Žē3-PUFAs as components of health foods and supplements.11 Of a total of 401 subjects were enrolled, however those, who on the basis of the Trial of Org 10,172 in Acute Stroke Treatment classification system,14 had moderate or high risk cardiac sources of embolism (n=127) were excluded. Patients who had undetermined stroke subtype (n=45: negative evaluation, n=19: two or more causes identified) or those who had rare causes of stroke subtype (n=10), such as moyamoya disease, arterial dissection, or venous thrombosis were also excluded from this study. Moreover, patients who received incomplete vascular imaging work-up (n=2) and those who had transient ischemic attacks with negative diffusion-weighted images (n=42) were not enrolled. Finally, a total of 156 patients were analyzed in our study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our Hospital. We received informed consent from all patients or from their caregivers.

Measurement of the degree of stenosis, stroke severity, recurrent stroke, and functional outcome

For extracranial arteries, the degree of arterial stenosis was measured according to the published method used in the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial.15 For intracranial arteries, the degree of arterial stenosis was measured based on the methods used in the Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease study.16 Vascular images were evaluated by two independent vascular neurologists, who were blinded to the clinical information. Inter-observer agreement on the presence of more than 50% stenosis and/or occlusion was excellent (kappa=0.95). The severity of neurologic deficits was determined using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) on admission.17 A recurrent ischemic stroke was considered in the presence of acute onset of focal neurological signs of more than 24 hours duration with evidence of a new ischemic lesion on CT or MRI scan, or when new lesions were absent but the clinical syndrome was consistent with stroke from admission to 3 months after the index stroke. Functional outcomes were assessed using the modified Rankin scale (mRS) 3 months after the index stroke.

Measurement of plasma phospholipid FAs composition

Blood samples for lipid profiles were collected from the patients within 24 hours of admission and at a fasting state of more than 12 hours. Blood samples were collected into EDTA-treated plain tubes. They were centrifuged to separate plasma or serum from the whole blood and then were stored at -70Ōäā until analysis could be performed. The methods for measuring FA composition have been described previously.11 Briefly, plasma total lipids were extracted according to the Folch method18 and the phospholipid fraction was isolated by thin layer chromatography using a development solvent composed of hexane, diethyl ether, and acetic acid (80:20:2). The phospholipid fractions were then methylated to FA methyl esters (FAMEs) by the Lepage and Roy method.19 The FAMEs of individual FAs of phospholipids were separated by gas chromatography using a model 6890 apparatus (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and a 30 m Omegawaz TM 250 capillary column (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA).20 Peak retention times were obtained by comparison with known standards (37 component FAME mix and PUFA-2, Supelco; GLC37, NuCheck Prep, Elysian, MN, USA) and analyzed with ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies). The average of duplicate measurements for each sample was calculated.11,21 Plasma phospholipid FAs were expressed as the percentage of total FAs. The sum (╬Ż) of 16:0 palmitic acid, 18:0 stearic acid, 20:0 arachidonic acid, and 22:0 behenic acid was defined as the ╬Ż saturated fatty acids; 16:1 palmitoleic acid, 18:1 Žē9 oleic acid, and 22:1 erucic acid were defined as the ╬Ż monounsaturated fatty acids; 18:2 Žē6 linolenic acid, 18:3 Žē6 ╬│-linolenic acid, 20:3 Žē6 dihomo-╬│-linolenic acid, and 20:4 Žē6 arachidonic acid were defined as the ╬Ż Žē6-PUFAs; and 18:3 Žē3 ╬▒-linolenic acid, 20:3 Žē3 5-8-11-eicosatrienoic acid, 20:5 Žē3 EPA, and 22:6 Žē3 DHA were reported as the ╬Ż Žē3-PUFAs.

Risk factors

Hypertension was defined as having resting systolic blood pressure Ōēź140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure Ōēź90 mmHg on repeated measurements, or receiving treatment with anti-hypertensive medications. Diabetes mellitus was diagnosed when the patient had fasting blood glucose level Ōēź7.0 mmol/L, or was being treated with oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin. Hyperlipidemia was diagnosed when the patient had low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol level Ōēź4.1 mmol/L or total cholesterol level Ōēź6.2 mmol/L. Patients were defined as smokers, if they were smokers at the stroke event or if they had stopped smoking within 1 year before the stroke event. Body mass index was estimated by dividing body weight by height (kg/m2). The presence of coronary artery disease was defined as a patient history of unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or angiographically confirmed coronary artery disease.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the Windows SPSS software package (version 18.0, Chicago, IL, USA). Independent t test, Mann-Whitney U test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc analysis, and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to compare the continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were expressed as means┬▒standard deviations (SD) or as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to determine the factors associated with NIHSS at admission. Functional outcome was dichotomized into good outcome (mRS <3) or poor outcome (mRS Ōēź3). Univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses were performed to determine the predictive factors for functional outcome. To assess the goodness of fit of the logistic regression model, Cox & Snell R Square was calculated and the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was performed. A two-tailed P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic data and the relationship between clinical data and fatty acid composition

The demographic data of study subjects and comparative analysis according to functional outcome at 3 months after index stroke are summarized in Table 1. The mean┬▒SD patient age was 65┬▒12 years. Of all patients, 56.4% (88/156) were male. The median NIHSS score was 3 [IQR, 2-5]. Of all patients, there were 60 (38.5%) patients with large artery atherosclerosis stroke subtype and 96 (61.5%) patients with small vessel occlusions. The means┬▒SD of proportions of EPA and DHA were 2.0┬▒0.7 and 8.9┬▒1.4, respectively. In the case of ╬Ż Žē3-PUFA, the means┬▒SD of proportion was 11.9┬▒1.9. Considering stroke subtypes, there was no difference between large artery atherosclerosis and small vessel occlusion stroke subtypes in terms of the proportion of EPA, DHA, or ╬Ż Žē3-PUFAs (Supplementary Table 1). Of the 156 patients, 122 (78.2%) patients had good functional outcome with means┬▒SD of EPA and DHA proportions of 2.1┬▒0.7 and 9.1┬▒1.3, respectively. The remaining 34 (21.8%) patients had poor outcome with a relatively smaller proportion of EPA (1.8┬▒0.6, P=0.032) and DHA (8.1┬▒1.3, P=0.001). The proportion of ╬Ż Žē3-PUFA in patients with poor outcome was significantly lower than that in patients with good outcome (10.8┬▒1.6 vs. 12.2┬▒1.9, P=0.001) (Table 1).

Association of fatty acid composition with stroke severity on admission, recurrent stroke, and functional outcome

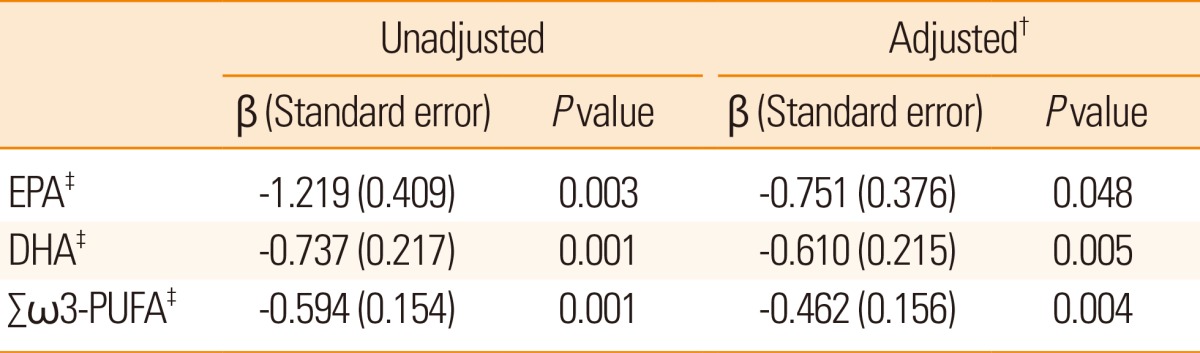

After adjusting for factors including age, sex, and variables with P<0.1 in the univariate analysis (stroke subtypes, hemoglobin, high density lipoprotein, high sensitivity C-reactive protein, fasting glucose, 16:0 palmitic acid, and ╬Ż saturated fatty acids), lower proportion of EPA and DHA were independently associated with stroke severity on admission (╬▓: -0.751, standard error (SE): 0.376, P=0.048 for EPA, ╬▓: -0.610, SE: 0.215, P=0.005 for DHA). Moreover, the ╬Ż Žē3-PUFA was significantly associated with stroke severity on admission (╬▓: -0.462, SE: 0.156, P=0.004) (Table 2) (Fig. 1). Considering stroke subtypes, DHA and ╬Ż Žē3-PUFA were correlated with stroke severity on admission, in both large artery atherosclerosis (even though it showed tendency for ╬Ż Žē3-PUFA, P=0.065) and small vessel occlusion, however EPA (Supplementary Table 2) did not appear to be correlated in multivariate linear regression analysis. There were six recurrent stroke cases and events, and EPA was relatively lower in the recurrent group compared to the non-recurrent group (1.6┬▒0.2 vs. 2.0┬▒0.7, P=0.006). However, the proportions of DHA and ╬Ż Žē3-PUFAs were not different between the two groups (Supplementary Table 3).

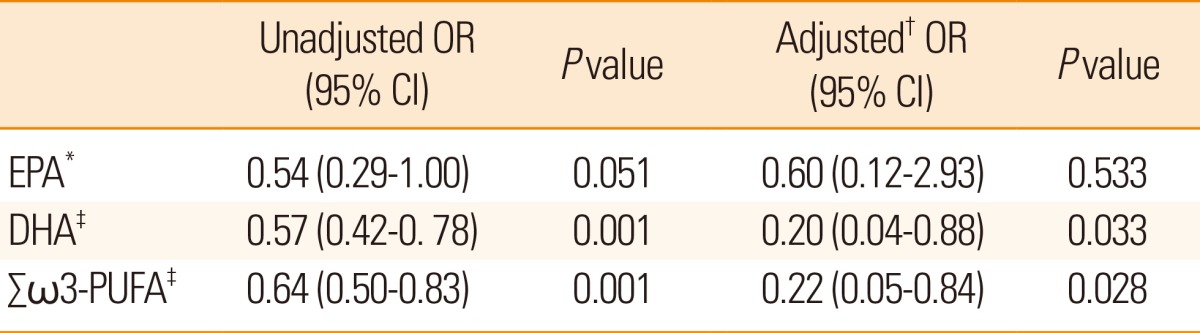

Regarding functional outcome at three months after index stroke, a lower proportion of DHA (odds ratio (OR): 0.20, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.04-0.88, P=0.033) and ╬Ż Žē3-PUFA (OR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.05-0.84, P=0.028) showed a significant relationship with poor functional outcome. However, EPA was not independently associated with poor functional outcome (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.12 -2.93, P=0.533) in multivariate analysis after adjusting for age, sex, smoking status, NIHSS score, stroke subtypes, or 16:0 palmitic acid (Table 3). Considering stroke subtypes, a lower proportion of DHA and ╬Ż Žē3-PUFAs was independently associated with poor functional outcome in both the large artery atherosclerosis subtype (OR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.42-0.93, P=0.023 for DHA, OR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.47-0.90, P=0.011 for ╬Ż Žē3-PUFA) and the small vessel occlusion subtype (OR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.28-0.85, P=0.012 for DHA, OR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.42-0.98, P=0.044 for ╬Ż Žē3-PUFA) (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

Our study revealed that Žē3-PUFAs, especially DHA, were associated with stroke severity on hospital admission and poor functional outcome even after adjusting for the NIHSS score, which is considered a strong predictive factor for stroke outcome. A few studies have previously reported such a relationship. For example, treatment with DHA-albumin complex in animal studies decreased brain injury after a transient and permanent focal cerebral ischaemia.22 DHA showed anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects by decreasing oxidative stress via activation of nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 and heme oxygenase-1 expression and by attenuating c-Jun phosphorylation, or the activating protein-1 signaling pathway.23 Consistently, studies in humans have produced similar results. One previous study in 281 Japanese patients with acute ischemic stroke diagnosed within 24 hours of onset, showed that the EPA/arachidonic acid (AA) ratio, DHA/AA ratio, and the EPA+DHA/AA ratio were independently and negatively associated with early neurological deterioration.24 Furthermore, a population-based study in the U.S.A, which included 2,692 elderly adults without prevalence of stroke or cardiovascular disease, revealed that higher plasma Žē3-polyunsaturated FAs (EPA, DHA, and total Žē3 FAs) were associated with lower mortalities.25 Overall, these previous studies showed that Žē3-PUFAs (especially EPA and DHA) were related to vascular outcome, which is in line with our study results. However, the reason why EPA was not independently associated with poor functional outcome in our study population remains to be elucidated. Possible hypotheses for these differences are as follows. DHA exerts vasodilating properties by stimulating nitric oxide release in the vascular endothelium, and hence may also be responsible for decreasing heart rate variability and potentially for dyslipidemia improvement, effects not observed by EPA.26 Loss of nitric oxide control, heart rate variation, and dyslipidemia may be related to poor vascular disease outcome,27 and our study results can be explained by the correlation observed with DHA, and not EPA, and with functional outcome. In addition, the difference in race and staple food of the study population could represent another possible explanation.

Our results demonstrated a relationship between Žē3-PUFAs and stroke severity on hospital admission and poor functional outcomes, in both the large artery atherosclerosis and the small vessel occlusion stroke subtypes. These associations may be due to the pleiotropic roles of Žē3-PUFAs. Žē3-PUFAs give rise to anti-inflammatory molecules (resolvins and protectins) through lipoxygenase or cyclo-oxygenase pathways.28,29 Resolvins or protectins play an important role in the resolution of inflammation, which decreases atherosclerotic changes and tissue injuries. Because cerebral small vessel pathologies such as lacunar infarction, white matter changes, and cerebral microbleeds are linked to inflammatory reactions30 and increase arterial stiffness31 caused by progressive atherosclerosis, these anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic effects of Žē3-PUFAs could explain the results observed in our study. Moreover, because progressive cerebral atherosclerosis is associated with a poor stroke outcome,32 our finding relative to the association between Žē3-PUFAs and stroke prognosis may be valid. In addition, the atherosclerotic plaque stabilization effect of Žē3-PUFAs may be an important mechanism. A previous study performed on patients awaiting carotid endarterectomy showed that plaques from patients treated with fish oil (1.4 g Žē3-polyunsaturated FAs per day) had a well-formed thick fibrous cap (i.e. less vulnerable) atheroma compared to that in patients of the placebo group.33 Pathologically, infiltration of macrophages was less severe in patients treated with fish oil.33 Furthermore, another prospective study confirmed that patients treated with fish oil had lower plaque inflammation and instability.34 Because the vulnerability of the atherosclerotic plaque is a very important determinant of thrombosis-related stroke, as well as the degree of arterial stenosis, our results relative to the relationship between stroke outcome and Žē3-PUFAs is within expectation. Lastly, a recent study revealed that Žē3-PUFAs enhanced cerebral angiogenesis in animal models,35 and because increased angiogenesis could augment brain repair and improve long-term functional recovery after cerebral infarction, these findings may support our study.35

One limitation of our study is that the blood samples were obtained from acute stroke patients on admission. Therefore, the fatty acids and their composition were not serially assessed during the time course of the stroke. Moreover, even though we prospectively enrolled our study subjects, our study design is mainly cross-sectional. In addition, the short-term of observation with a small sample size is another limitation of this study. Further studies with a long-term follow-up and larger population size are needed. Finally, our study design was not that of a randomized control study. Furthermore, because stroke severity on admission correlated with both lower proportion of Žē3-PUFAs and functional outcome at 3 months, there could be a bias due to the interaction between severity on admission and Žē3-PUFAs. That is, there may be a possibility that the functional outcome at 3 months is only weakly associated with Žē3-PUFAs. Therefore, a causal relationship between Žē3-PUFAs and poor outcome is still unclear. Careful interpretation of our study is needed.